Everybody likes to have options to choose from, or at least they think they do. That’s part of what led some automakers to bet heavily on plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, or PHEVs, which offer consumers a way to get a sampling of the EV experience without jumping fully in.

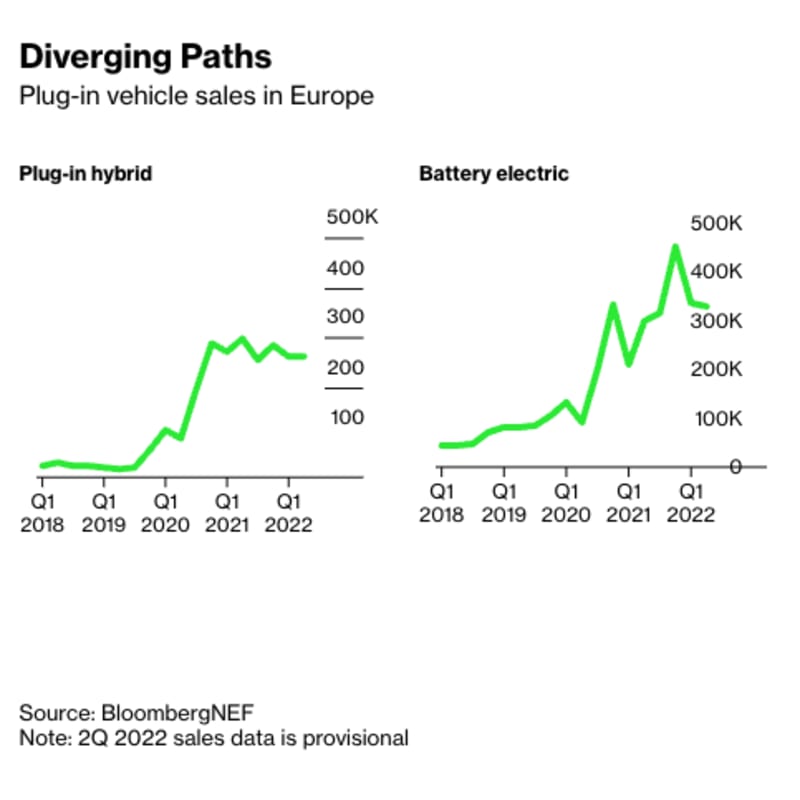

hybrids and battery-electric vehicles, or BEVs.

Country-level data paints an even starker picture. Sales of PHEVs in France fell 28% in June. In Germany — another former stronghold for the technology — registrations dropped 16%. In the UK, plug-in hybrids were neck-and-neck with BEVs as recently as 2019. Now, two battery-electric cars sell for every one PHEV.

Some of this is to be expected. In 2020 and 2021, automakers had to meet Europe’s stricter CO2 targets for new vehicles, and plug-in hybrids were treated favorably under the regulations. Many automakers didn’t have their new BEV architectures fully ready. When faced with two options — to market fully electric vehicles underpinned by modified internal combustion platforms, or PHEVs — many opted for the latter.

Europe’s vehicle CO2 regulations don’t tighten again until 2025. As more automakers get their fully electric platforms ready for model launches, BEVs look poised to continue their ascendency of the sales charts. Consumers are clearly ready, with wait times already stretching well into next year for most of the popular fully electric models in Europe.

Many PHEV owners are happy with their cars. But from a policy perspective, there’s an elephant in the room: drivers often don’t end up charging these vehicles all that frequently. A recent study of 9,000 vehicles from the International Council on Clean Transportation found that real-world fuel consumption from PHEVs was 2.5 to 5 times higher than what’s approximated under official laboratory testing procedures.

That gap between theory and practice is part of the reason national governments are cutting purchase subsidies for PHEVs faster than for fully electric models. The UK, for example, eliminated purchase subsidies for plug-in hybrids in 2018, while Germany announced just this week that PHEV subsidies will end this year.

One critical distinction here is that the share of electric kilometers driven on a PHEV depends heavily on who owns it. Among privately owned vehicles, the ICCT study found real-world electric-driving share was 45% to 49%. Not bad, though still short of what the official test cycles assume. For company cars, that dropped to a dismal 11% to 15%. Company vehicles are a huge part of the market in Europe, accounting for more than half of new-car sales in many countries.

Upcoming policy changes could further erode the case for PHEVs. The European Commission is expected to introduce new “utility factors” for PHEVs from 2027. These are the values intended to reflect how often the vehicles are driven in electric mode, and critically, what CO2 emissions value they’re assigned.

The goal for the regulation is to use real-world driving behavior from both private and company-owned vehicles to set the values, using on-board monitors. Unless something dramatic changes in the next few years, this will make PHEVs a less attractive way for automakers to meet emissions regulations. Manufacturers will see this change coming down the road and start to allocate investments accordingly.

Relatively strong sales of plug-in hybrids in China are keeping the global numbers afloat for now. PHEV sales there more than doubled last year, led by offerings from BYD and Li Auto, though even that wasn’t enough to keep pace with growth in BEV demand. China has more high-rise apartment dwellers with limited home-charging options, but the government is making a huge push to build out public-charging options and help keep the BEV market expanding quickly. The municipal government in Shanghai is also set to remove favorable treatment for PHEVs beginning in 2023, and others could follow.

If plug-in hybrids are a bridge, it’s starting to look like a short one.